The concept of ‘set point weight’ describes how the body maintains its weight around a biologically predetermined point, or a ‘set point.’

My first informal encounter with set point weight theory was actually Geneen Roth, who refers to it as your ‘natural weight.’ However, Set Point Weight Theory in clinical terms was pioneered by researcher Jeffrey Friedman and is also commonly associated with the popular book Health at Every Size by Linda Bacon.

No matter which thought leader you turn to, the message is the same: stop fighting against your biology by forcing weight loss through dieting. It does not work. Instead, work with your body, heal your relationship with food, and allow yourself to settle upon a comfortable weight within your natural range.

What Is Your “Set Point Weight”?

Your set point weight, also known as your settling point weight or natural weight, is the weight range that your body gravitates to. Set Point Weight Theory is part of the explanation behind why restrictive diets don’t work and how weight loss primes the body for weight regain. Your body works hard to achieve balance (homeostasis) and your set point weight is a manifestation of this biological drive.

Set Point Weight Theory suggests that your body has a natural weight range, kind of like a personal comfort zone. While your natural weight is influenced by the foods you eat and how much you exercise, your biology plays a starring role.

Imagine your body weight being somewhat like a thermostat, set at a certain range. This range is influenced by a mix of hormones, genetic factors, and environmental/external factors like your diet, according to a study published in the journal F1000 Medicine Reports.[1] Despite even extreme changes, your body will work hard to defend its place at a specific set point weight.

To illustrate Set Point Weight Theory, let’s look at a population of rural Gambian women who experienced repeated annual food shortages over a period of 10 years. Despite repeatedly losing and gaining weight (“weight cycling”) during those 10 years, their minimal body weight remained fairly stable — within 3-4 pounds, according to a study published in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.[2]

Despite true food insecurity, their bodies adapted to maintain the same set point weight throughout years of seasonal fluctuations and food shortages. This is a perfect example of how rigorously your body will defend its set point weight.

Factors that Influence Your Set Point Weight

Before we discuss whether or not you can change your set point weight, let’s discuss the factors that influence it to begin with. As per usual, I will start by addressing biological factors before the psychological factors. Although eating psychology is my passion, no amount of psychological finesse can outsmart your biology, so let’s start there.

Hormones: Leptin and Ghrelin

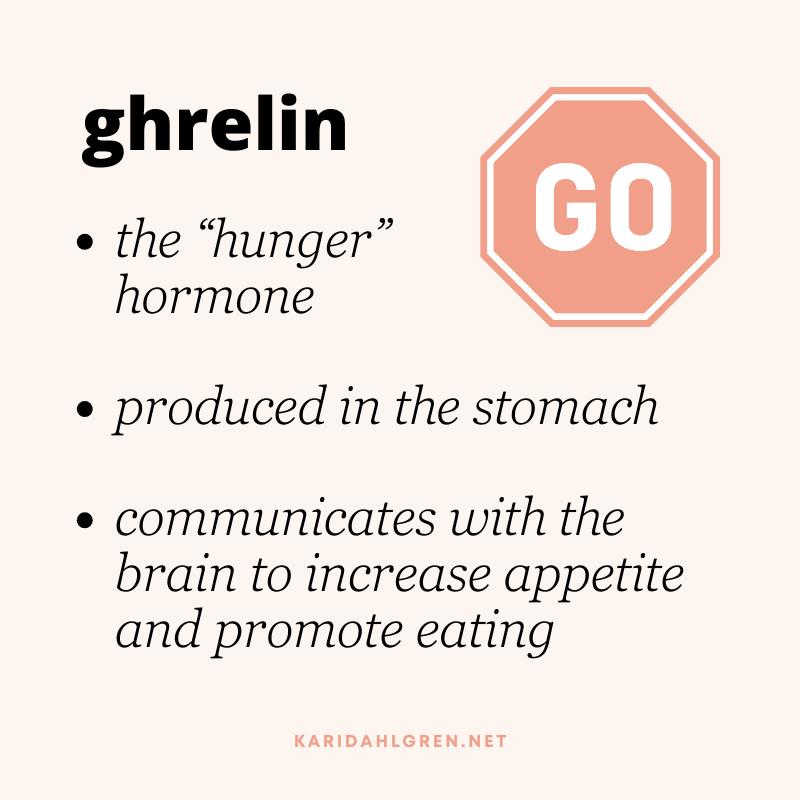

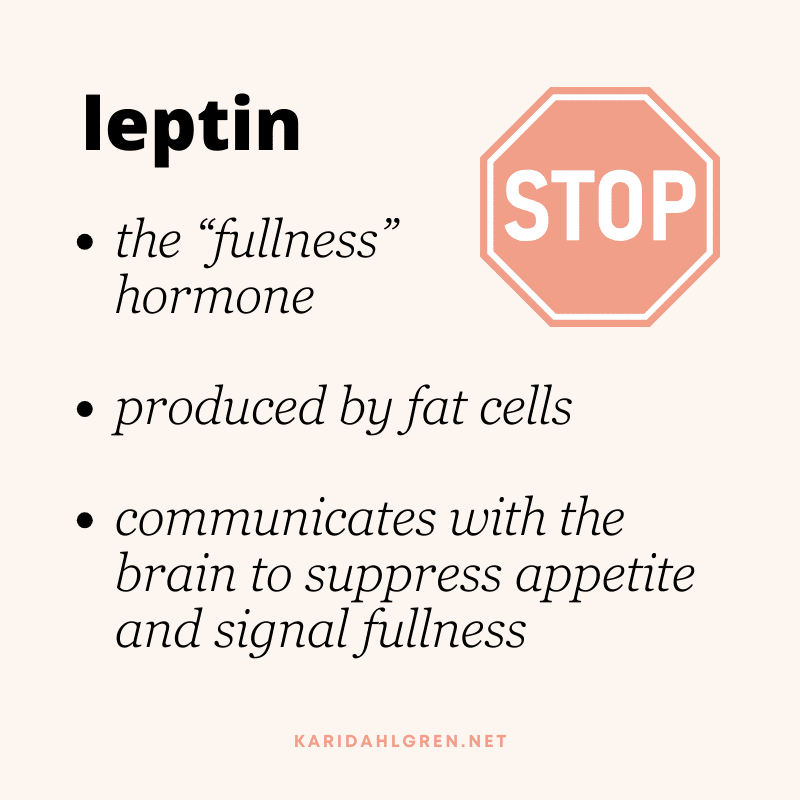

Your hormones play a critical role in set point weight theory — specifically leptin and ghrelin, the fullness and hunger hormones, respectively.

- Leptin, produced by fat cells, communicates the body’s energy sufficiency to the brain. High levels of leptin reduce appetite, which helps maintain set point weight by signaling when the body has enough energy reserves. This regulation of appetite helps balance long-term energy and body weight.

- Ghrelin, produced in the stomach, signals hunger to the brain. Its levels rise to initiate eating and fall after consuming food. By regulating hunger and food intake, ghrelin plays a key role in maintaining set point weight, addressing short-term energy needs and overall energy balance.

When the balance between leptin and ghrelin is disrupted, it can potentially shift your set point weight. For instance, after periods of restrictive dieting, ghrelin levels rise and leptin levels fall to motivate eating, potentially contributing to weight regain.[3]

When you try to lose weight through restrictive dieting, your body essentially fights back to maintain its set point weight by adjusting its hormones. Researchers even found that, one year after weight loss, leptin levels were still lower than before participants started dieting, setting the stage for long-term weight regain and set point weight maintenance.[3]

Genetics & Set Point Weight Theory

One interesting aspect of Set Point Weight Theory is the “thrifty gene” hypothesis.[4] This idea suggests that some of us are genetically wired to be more efficient at storing fat and using food energy.

While the “thrifty gene” is helpful during periods of food scarcity, it doesn’t really help in today’s world where high-calorie treats are just a supermarket away. However, your body’s natural set point weight is not all about genetics.

The environment you live in — including lifestyle choices like diet and exercise — plays a significant and perhaps even more influential role than genetics.[1] For example, while the “thrifty genotypes” might be predisposed to a higher set point weight, this only really becomes noticeable when a high-calorie diet is consumed.[4]

Having the “thrifty” gene doesn’t promote excessive eating — it promotes the likelihood that excessive eating will result in excessive body fat. It’s as if our genetic predispositions are waiting backstage and our lifestyle choices are what bring them into the spotlight.

External Factors (Including Your Diet) Influence Your Natural Weight

This is where the choices we make every day come into play. The food we eat, how much of it we consume, and the overall patterns of our diet can shift where our weight settles within its natural range. It’s a delicate dance between our inner biological world and the external choices we make.

Here are some external factors that can influence your set point weight:

- Diet: A diet full of energy-dense, hyperpalatable foods can cause overeating, weight gain, and eventually a higher weight settling point.[5]

- Exercise: The more you exercise, the better your body gets at maintaining the same level of overall energy use.[6] This means that reaching or maintaining your set point weight isn’t just about exercising more.

- Stress: Long-term stress can lead to insulin resistance and weight gain.[7] Furthermore, stress can lead to emotional eating where food is used as a buffer or coping mechanism.

- Sleep: Poor sleep can disrupt hormones like leptin and ghrelin, leading to increased appetite and potential weight gain, thereby affecting your set point weight.[8]

- Socioeconomic status: This can influence access to healthy food options and opportunities for physical activity. Lower socioeconomic status may limit these opportunities, potentially leading to an elevated set point weight.

Psychological Factors

There are many psychological reasons for overeating, and the body may adapt to persistent overeating by settling upon a higher set point weight. When eating becomes a coping mechanism rather than a source of nourishment (which can and should involve joy and satisfaction, by the way) it can gradually push your set point weight higher.

On a similar note, your perception of your body is another psychological aspect influencing your set point weight. A negative body image can lead to excessive dieting, excessive exercise, or the opposite – neglecting physical activity and gentle nutrition. These extremes can disrupt your body’s natural weight regulation mechanisms.

Can Your Set Point Weight Change?

Yes, your natural weight or set point weight can change. Studies have found that, instead of having one set point weight, your body has many different “settling points.”[9] That’s why your set point weight is a range. Surprisingly, it’s easier to explain what doesn’t change your set point weight before explaining what does.

Eating less (dieting) and exercising more does not necessarily lead to a lower set point weight.

Robust clinical evidence shows that restricting your diet causes biological backlash (e.g. persistent hormonal changes) that favors weight regain.[3], [10], [11] These hormonal and metabolic adaptations are your body’s way of trying to get back to its set point weight. In some ways, dieting can be viewed as a way to increase your set point weight – not decrease it! The human body is not wired to favor weight loss.

From an evolutionary standpoint, the ancestors that had extra body fat were the ones who survived. Millions of years of evolution has favored organisms that respond to famine (such as periods of restrictive dieting) with metabolic adaptations that preserve body fat, not release it.[12]

As for exercise, a sustained increase in exercise may not help you reach a new set point weight either because, once again, your body adapts![13] This does not mean exercise should be neglected as it provides enormous health benefits — as long as you aren’t overexercising.[14]

Now, if dieting and exercise aren’t the keys to reaching or maintaining your set point weight, what is?

How to Reach or Maintain Your Set Point Weight(s)

There are steps you can take to encourage your body to settle upon a different weight within your natural range, especially if you believe you’re above the set point weight that is healthiest for you. While no one really knows what their exact set point weight is, those who are overweight know when a specific weight just doesn’t feel good.

Fortunately, there are gentle steps you can take to encourage your body to settle upon a healthy weight within your natural range:

1. Stop Restrictive Dieting

Embracing a more flexible, intuitive approach to eating is key. Restrictive diets lead to a rebound effect, causing weight gain and hormonal imbalances. Instead, focus on eating what appeals to you when you’re hungry and stopping when you’re full.

While it may sound radically simple, it is not the only step! But it is a crucial step towards healing your relationship with food and allowing your body to settle upon a comfortable weight.

Embrace All Foods as Equal

Categorizing foods as ‘good’ or ‘bad’ can lead to an unhealthy relationship with eating. By viewing all foods as equal, you remove the guilt associated with eating certain items. This decreases the inclination to restrict your diet, which will have a positive effect on finding or maintaining your set point weight.

Remember, your body has many different settling points, so it’s not about finding the perfect size. Rather, it’s about making peace with food, finding physical and mental health as your body regulates itself.

Focus on Body Acceptance Over Weight Loss

If you want to discover your set point weight, it’s best to reframe your mindset to focus on health and body acceptance above weight loss. It’s okay to desire weight loss, especially if you know you’re above your natural weight, but allow weight loss to be the byproduct of healing your relationship with food rather than the primary goal.

Here’s a video where I talk about why it’s okay to desire weight loss while eating intuitively:

I created this video because I noticed that many of my coaching clients were asking about the desire to lose weight. To my surprise, they all had something in common: they had worked with an anti-diet coach who told them they weren’t allowed to desire weight loss — at all.

While I agree that a fixation on weight loss is counterproductive, there is no need to feel ashamed for wanting to lose weight, especially if you know in your heart that you’re above your natural weight. I’d much prefer you to treat yourself with compassion than remain stuck in a shame storm.

Relax More, Metabolize Better

Stress causes a cascade of unwanted and unhealthy events, including weight gain.[7] Though your body is efficient at finding its way back to its natural weight after a period of stress-induced weight gain, chronic long-term stress can force your body into a higher set point weight.

Fortunately, when you focus on relaxation, you improve your metabolism and (as a nice little side bonus) digest your food better, too.[15] Hopefully this motivates you to find ways of relaxing and reducing stress.

It may be as simple as choosing yoga over a bootcamp style exercise class, or it may require more involved changes like finding a new job (if your current occupation is the source of your stress).

Exercise in Balanced Ways

Incorporate exercise as a part of a healthy lifestyle rather than as a tool for weight loss. Choose activities you enjoy and focus on the pleasure of movement rather than the calories burned. This is known as intuitive movement.

You do not need to exercise excessively to reach your natural weight. We already discussed how excessive exercise actually causes your body to adapt and maintain its current set point weight.[6] Excessive exercise is stressful, so why would your body want to dump energy reserves (read: body fat) while under stress?

Add Joy to Your Life Outside of Food

When we don’t get joy from our lives, we will compulsively seek it through food. This is heavily tied into the phenomenon of hedonic eating, or “eating for pleasure.” To help avoid this pattern, add pleasure to your life outside of food. This will make it easier for your body to reach its set point weight by addressing the psychology of overeating.

Find Satisfaction in Eating

Satisfaction is something you can and should get from eating too, though. If you finish a meal and feel full but unsatisfied, it’s probably because you ate something according to food rules instead of what you really wanted.

Eating should be a pleasurable experience. Savor your meals, appreciate the flavors, and eat in a pleasant environment. Enjoying your food helps in cultivating a positive relationship with eating and supports your body in naturally regulating its set point weight.

Settling Upon a Healthy Weight in Your Natural Range

Embracing your body’s natural set point weight is about finding a harmonious balance between your biological needs, psychological well-being, and lifestyle choices. It’s not about rigid diets or punishing exercise regimes, but rather about listening to and respecting your body’s cues. By cultivating a compassionate relationship with food and your body, you allow yourself to live a fuller, healthier life, where weight management becomes a natural outcome of self-care.

- Müller, Manfred J et al. “Is there evidence for a set point that regulates human body weight?.” F1000 medicine reports 2 59. 9 Aug. 2010, doi:10.3410/M2-59

- Prentice, A M et al. “Effects of weight cycling on body composition.” The American journal of clinical nutrition 56,1 Suppl (1992): 209S-216S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/56.1.209S

- Sumithran, Priya et al. “Long-term persistence of hormonal adaptations to weight loss.” The New England journal of medicine 365,17 (2011): 1597-604. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1105816

- Walley, Andrew J et al. “The genetic contribution to non-syndromic human obesity.” Nature reviews. Genetics 10,7 (2009): 431-42. doi:10.1038/nrg2594

- Morris, Margaret J et al. “Why is obesity such a problem in the 21st century? The intersection of palatable food, cues and reward pathways, stress, and cognition.” Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews 58 (2015): 36-45. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.12.002

- Pontzer, Herman et al. “Constrained Total Energy Expenditure and Metabolic Adaptation to Physical Activity in Adult Humans.” Current biology : CB 26,3 (2016): 410-7. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.12.046

- Björntorp, P, and R Rosmond. “Neuroendocrine abnormalities in visceral obesity.” International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders : journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity 24 Suppl 2 (2000): S80-5. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0801285

- Mosavat, Maryam et al. “The Role of Sleep Curtailment on Leptin Levels in Obesity and Diabetes Mellitus.” Obesity facts 14,2 (2021): 214-221. doi:10.1159/000514095

- Ganipisetti VM, Bollimunta P. Obesity and Set-Point Theory. [Updated 2023 Apr 25]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK592402/

- Dulloo, A G, and J-P Montani. “Pathways from dieting to weight regain, to obesity and to the metabolic syndrome: an overview.” Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity 16 Suppl 1 (2015): 1-6. doi:10.1111/obr.12250

- Sumithran, Priya, and Joseph Proietto. “The defence of body weight: a physiological basis for weight regain after weight loss.” Clinical science (London, England : 1979) 124,4 (2013): 231-41. doi:10.1042/CS20120223

- Betsy B. Dokken, Tsu-Shuen Tsao; The Physiology of Body Weight Regulation: Are We Too Efficient for Our Own Good?. Diabetes Spectr1 July 2007; 20 (3): 166–170. https://doi.org/10.2337/diaspect.20.3.166

- Pontzer, Herman et al. “Constrained Total Energy Expenditure and Metabolic Adaptation to Physical Activity in Adult Humans.” Current biology : CB 26,3 (2016): 410-7. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.12.046

- Colledge, Flora et al. “Excessive Exercise-A Meta-Review.” Frontiers in psychiatry 11 521572. 20 Nov. 2020, doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.521572

- Cherpak, Christine E. “Mindful Eating: A Review Of How The Stress-Digestion-Mindfulness Triad May Modulate And Improve Gastrointestinal And Digestive Function.” Integrative medicine (Encinitas, Calif.) 18,4 (2019): 48-53.

![best seller [cover of Why We Do the Things We Do]](https://karidahlgren-net.b-cdn.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/why-we-do-the-things-we-do-1.png)

I enjoy your wisdom so much.

At age 67 I am the heaviest I have been but suddenly 2 weeks ago there was a switch. An awareness. This only happened after I accepted that at this highest weight I found I loved my body to the fullest and was grateful to just experience my soul in a body…. To experience the five senses it allows and all other human experiences.

I became aware of my hunger full hormones. They had not be listened to for a long time since my mind was on dieting all the time. I have had a broken arm for 5 weeks which caused me to slow down and really listen to my body’s signals. At first I started the hamster wheel thinking of “you better go on a diet”!Using one arm to lift all the extra weigh was a wake up call that I am not comfortable with the extra weight (had become numb to facing another diet which was all the weight gain).

So with your open mind idea about no restrictions caused me to not panic about I must restrict and I am now happy with eating much less and am satisfied after small amounts of food . My weight as a result is dropping at a nice slow pace. I love also exercising to what feels good. I am in physical therapy but love to walk so that is what I am doing! Thank you Kari.

Ohhh this is so good! Congrats on the milestone Janet! I especially love this: “dropping at a nice slow pace.” That is perfect. Slow weight loss is the most sustainable! But weight loss aside, all of this started with acceptance, and that is beautiful. Thanks for sharing your story Janet!!